We thought it would be a quiet destination for dinner by the water, but that evening it was teeming with throngs of tourists. We were in Kowloon, Hong Kong, having taken an Uber to a normally serene spot where, it turned out, a bustling Christmas celebration was underway. People were everywhere. All of the local restaurants were full. And the normally empty lawn housed a hectic community gathering.

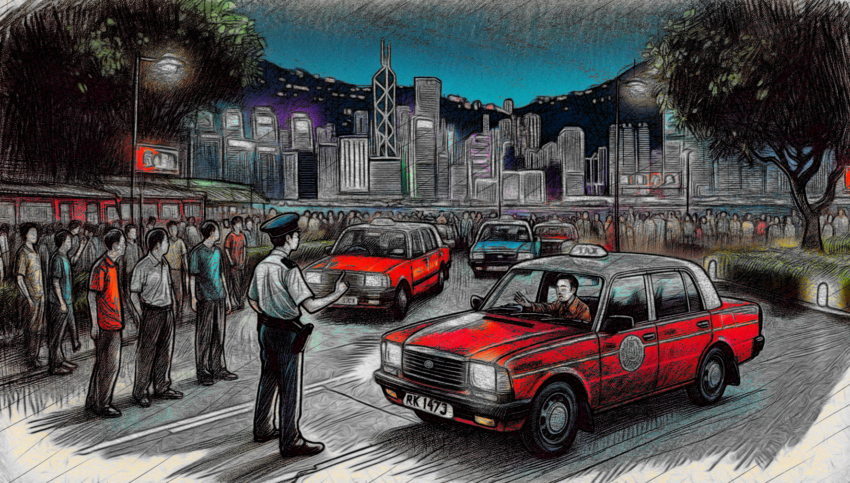

So we set out to find a taxi to take us elsewhere. But hundreds of other people were also looking for a taxi, and the taxi stands were just as congested and chaotic as everything else.

I’m from New York though. I know how to do this, I thought. And sure enough, before long I spotted a cab just a few feet away as its driver was dropping some people off. Vaguely aware of the police milling about, I nonetheless made eye contact with the driver, silently asking: “Are you available?”

He nodded, so we jumped in the passenger-side door.

And a police officer walked around to the driver side.

We sat in the back seat of the motionless cab as we learned that we were in a no-stopping zone, where the driver was forbidden to pick up passengers. I had already observed the police so I felt terrible. I should have known.

But should I really?

My friend, a local, felt even worse.

My friend thought the fine might exceed HK$100, only about US$13 and hardly exorbitant, but hefty nonetheless in light of the low cost of taxis in Hong Kong. A typical local ride might run only a few US dollars, so $13 could have been a couple hours’ work.

I rolled down my window, hoping the presence of a westerner might evoke some leniency from the police officer.

I waited.

I toyed with the idea of snapping a photo of the officer, but I wasn’t sure of my legal footing. (I also toyed with the idea of taking a surreptitious shot, but nixed that on the general principle of not doing anything that I was purposely trying to hide from the police.)

So instead I just waited some more.

I hoped to learn that the driver had only been given a warning.

When we finally got underway I found out that he had instead been fined a whopping HK$560, or US$70! That was a whole day’s work for him, maybe more.

My friend and I talked it over during the short drive, and I decided to pay the driver’s fine. After all, he had stopped for me. Besides, I could afford it.

But should I have paid it?

Certainly I couldn’t be held responsible. I was a foreigner, after all, unaware of local parking regulations. And I wasn’t the one driving. For that matter, perhaps the die had already been cast when the driver dropped off the previous passengers. Maybe the fine had nothing to do with me.

My friend who felt worse was even less responsible. Though she could have known the local regulations, she wasn’t the one who hailed the cab. I was.

Still…

Still what?

We were involved. I paid the fine both because I could and because I was involved.

I actually suspect that many people think they feel responsible when what they really feel is involved.

Responsibility and involvement are not always easy to tease apart, particularly because they often have similar or even the same consequences.

In terms of those consequences, two issues seem relevant to me.

The first is reminiscent of questions surrounding tipping and charity: Does involvement create obligation the way responsibility does?

I tip people not because they deserve the money more than anyone else, or even because they necessarily deserve it all (for instance, I may have aided and abetted the enemy by tipping). Rather, I tip because proximity creates involvement. And, for me, involvement pushes me toward obligation.

So maybe the same dynamic was at play with the Hong Kong taxi driver. Perhaps my involvement created an obligation on my part.

Of course there’s another possibility: Maybe involvement creates not obligation but guilt, and I was acting out of (perhaps misplaced) guilt.

The second issue is related: Does involvement convey moral culpability the way responsibility does. I don’t think so, and that’s the primary reason I think it’s so important to distinguish between responsibility and involvement: We should strive not to be responsible, but there’s nothing inherently wrong with being involved.

In the case of the taxi driver, the stakes were pretty low. I’m fairly sure I didn’t do anything wrong, but even if I did, it was, at most, a minor transgression. It’s not the kind of thing that requires any sort of serious moral realignment on my part.

What about the beggar girl? I gave her some money (against my host’s wishes). But sometimes I see children and don’t give them money. Is that immoral? If I’m responsible, maybe it is; if I’m merely involved, maybe not.

Interpersonal relationships are similar. When someone we care about is unhappy, we usually want to help. But success often depends on first separating our involvement from any responsibility we may have.

And what about war? No one wants to be involved, but we may have no choice. No one wants to be responsible, and there we do have a choice.

In the end, I think it’s all too easy to mistake involvement for responsibility. And when we do, we are liable to react in inappropriate and even destructive ways.