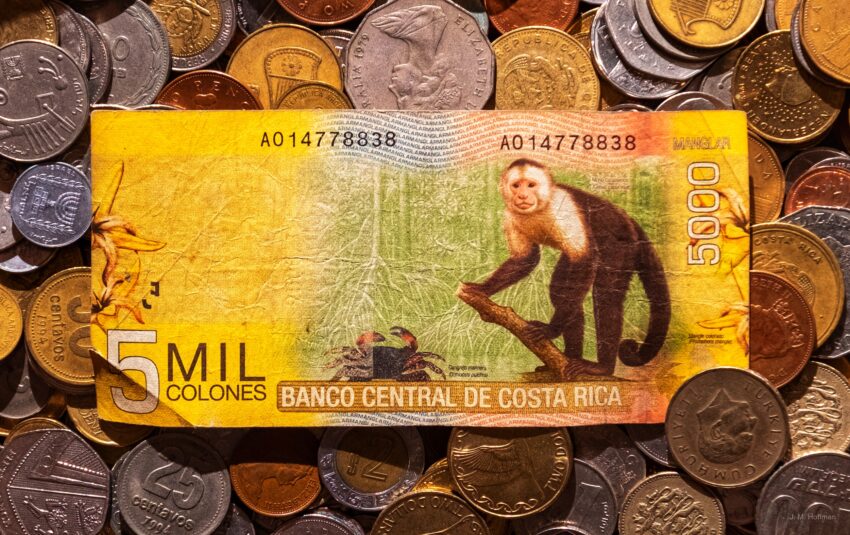

What could represent Costa Rica better than the white-faced capuchin monkey that adorns the 5,000-colónes note? The bill even teaches a little, listing both the Spanish and Latin names for the animal. The other elements in the scene, a red mangrove and a marine crab, get similar treatment. And as on other bills, the menagerie here wraps around, with each side picking up where the other leaves off.

Costa Rica is like that: verdant, full of nature, creative, and always offering something new.

The bill is worth roughly US$7.50, or about what it costs a local family of five to gain entry into the popular Manuel Antonio National Park. I was a foreigner, so I paid a little more, but it was certainly worth it. (I used my 5,000 note for a latte and croissant.)

The front of the bill features Alfredo González Flores, who served as president of the country from 1914 until he was forcibly removed in a coup d’état led by his secretary for war and the navy.

Costa Rica no longer has such a secretary, because it no longer maintains a military. In 1948, president José Figueres publicly smashed a hole in the wall of the imposing military headquarters in the capital city of San José, symbolically demonstrating the end of the country’s armed forces. Then he handed the building’s keys to the minister of education, with instructions that it be converted into a museum. The nation’s military budget, he ordered, would be redirected toward healthcare, education, and environmental protection.

The healthcare and education make Costa Rica a wonderful place to live and a delight to visit, and the environmental protection is what turned Costa Rica into the world’s first popular ecotourism destination, where people can see things like the capuchin monkey.